Megillot/Scrolls

Etti Abergel, Avraham Eilat, Benni Efrat, Arie Aroch, Moshe Gershuni, Nurit David, Jack Jano, Sigalit Landau, Assi Meshullam, Michal Na’aman, Moshe Kupferman, Gabriel Klasmer, Tal Stern

Noa Melamed

Introduction

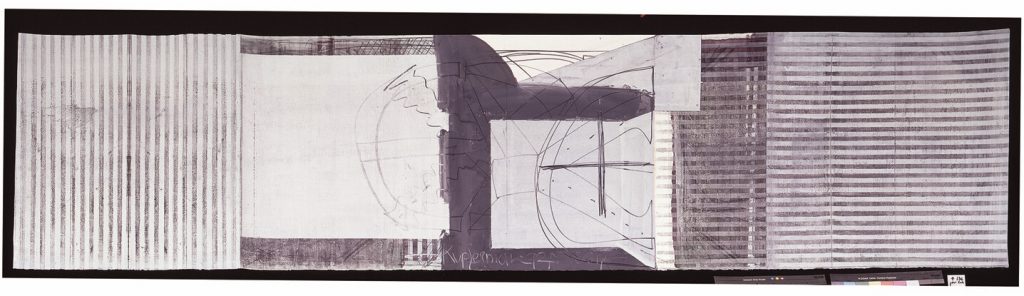

My connection with Kupferman and his work began thanks to Avi Hurwitz, upon whose death Kupferman painted the series of Megillot, two of which open this exhibition. The hall adjacent to the atelier was constructed in the early 1990s. For that occasion Avi curated the exhibition “Encounters.” I tried to help. The connection intensified, and I became a frequent visitor to the studio. In 1998, upon the inauguration of the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme, Paris, Kupferman was invited to present his works. I joined him on that trip. It was an exhibition of his Megillot (paper scrolls) co-curated by Yona Fischer and Nathalie Hazan-Brunet. For me, it was a journey of learning and experience, attentiveness and observation. It was a twofold observation of the many works we saw in various exhibitions and of the way in which Kupferman observes. I would like to extend my gratitude for the opportunity to revisit the Megillot of Kupferman and others.

In the mid-1970s Kupferman worked at the Jerusalem Print Workshop, and brought paper leftovers back to the studio, on which he drew. These were strips of paper, 70 cm to 1.10 m long, whose maximum width was 10 cm.

By that time the repetitive gesture had already become a constant element in his artistic vocabulary, but the paper format, in this case, emphasized the horizontal orientation.

Since 1979 these strips were painted on both sides in Kupferman’s typical mode of paper processing; some of them are even signed on both sides. The work process was supplemented by the use of color. In 1987 the strip increased in size and was named Megillah. The length of the first Megillah did not exceed 1.20 meters, but later they were to reach two and even three meters and more.

A major feature distinguishing the Megillah from any other format is the fact that it unfolds and is “inscribed from side to side—from left to right (Kupferman was left-handed), not continuously, but rather in a manner which is repeatedly constructed in the space. These papers do not offer a single focus, nor do they introduce a counterpoint option, of one against the other, but rather a sequence of situations side by side, one following the other; actions which evolve one from another. “Concatenation,” was Kupferman’s name for a sequence of actions naturally leading from one to the other. This is a significant element, innate to his work.

The point of departure, the initial gesture, prompts a response via another, at times contradictory, gesture. The situations generated by the previous act, which spawn the next, form the sum total, the totality which is the painting. It is a chain reaction which leads to an existential claim, where awareness of the choice of the next phase and its relation to the antecedent one are crucial.

In order for forward motion to be created, one must go back. The word forward (kadima) includes the notion of “fore” (kdam). Progress (kidma) must precede (likdom). The Megillah scroll evolves through movement forward and back (left and right), on and behind the paper.

According to Yona Fischer, Kupferman’s work is “rooted … in thought and deed, it is bound up with a way of life characterized by a constant regeneration.”1

Binding the past with the present as an opening to the next step reflects Kupferman’s worldview: a basic belief in a continuum and a process of tikkun. According to his perception, movement or innovation must result from habit and repetition. “Painting is a routine: incessantly repeating a certain number of gestures; knowing how to use a repertoire of forms whose effectiveness has been tested so many times … adopting new means only out of strict necessity.”2

The title Megillot and the elongated format take us back to ancient times, to texts inscribed on parchment by scribes and copyists of the Scriptures, handed down from one generation to another, spread out, revealed, read, rolled back, and shut: Torah scrolls, the Hidden Scrolls, the Holy Scriptures, and secret ciphers. (Today, in the computer era, we have resumed scrolling up and down, left and right).

The scroll, in its very form, embodies the potential of movement, of closing and opening, exposure and concealment. The rolled up scroll, with the feminine Hebrew name Megillah and rounded form, treasures a secret.

The concealment and revelation, the inter-generational affinity, the progression forward and back—these are the elements comprising the exhibition. The presented works maintain a link with the past, with the progress of time, and its twists and turns. They whisper and cry out, protest and praise, touching in various manners upon sanctity and impurity, body and soul, the private and the collective, the raw material and the material of thought.

A significant place in Arie Aroch‘s oeuvre is reserved to recollection, citation, and dialogue with objects and works of art which often verge on the popular and traditional. In the two works in the current exhibition Aroch relies on forms extracted from Christiaan Ludolph Reinhold’s late 18th century handbook for painters. In one, a line exercise with a figure 8 transforms into a boat, whereas in the other, ornamental lines intersect with the contours of a profile which evolved from the figure 2 drawn from a child’s scribbles around the illuminations of the Sarajevo Haggadah.

In both works, the beautiful, flowing, continuous, undulating forms encounter additional, personal and private content. Under the boat, a line from a popular Jewish poem about reconciliation between spouses is handwritten in Yiddish. Alongside the ornaments emerges a profile, or rather—two reversed, mutually-complementary profiles.

The love of writing also nourishes Tal Stern‘s scroll. Stern, however, neutralizes his signs of conventional meaning, and they are left as fine black shapes on the white paper; forms gathered side by side, lines upon lines and paragraphs. Unlike a scribe who cannot err, Stern creates and invents each letter anew as it evolves, and that letter leads to the next in a sequence, as in meditation or prayer, yet one where the mumble and not the word, the rhythm or the sound, nor the content or meaning—the how and not the what—generates the response.

The operating hand and its “mechanical” response directs Gabriel Klasmer‘s paintings as well. Klasmer paints with the aid of various devices which ostensibly distance painting from its romanticism. His work is based on repeated uniform movement which eliminates the “personal handwriting.” Many of his series are based on a horizontal, long and narrow format. The viewer is faced with a repetitious, ongoing, fixed single gesture. The squeegee movement generates lines, rows, a painting. It is an abstract painting which strives to steer away from any image, but nevertheless an image and what an image. A prayer shawl (tallith) unfolds from the quintessentially modernist painting, fluttering like a flag, like a covering, like an object.

The scroll is significantly present in Avraham Eilat‘s work. In many series he works in a horizontal narrow and ongoing format, and they progress from side to side; scrolls of fire, scrolls of brain and muscles, black scrolls and photographic scrolls which juxtapose situations and sites. The scrolls in the current exhibition are a part of a large-scale series, painted in brown ink on paper. They call to mind Egyptian painting, comics, or Meir Gur Arie’s pioneer paper cuts. It is a human chain of suffering and pain, war and disaster, and at the same time—an attempt to survive and overcome. The curse of the banishment from Eden reverberates throughout the work: “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, and in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children.”

The desire to keep moving and creating is often discernible in Sigalit Landau‘s work. The triptych in the exhibition is an excerpt from a video work which was presented in her solo exhibition, “The Endless Solution,” at Tel Aviv Museum of Art’s Helena Rubinstein Pavilion in 2004. The photographs conceal a persistent, ongoing process endeavoring to outline a sign in the sand opposite and alongside the sea which washes it off, erasing it. Two women lean down toward the sand as in an ancient ritual dance, each to herself, marking an ongoing wavy line in the sand. They progress one towards the other; their lines intersect, producing a new form which curls like a DNA helix or a sequence of the infinity sign. A dance and a sign dedicated to the memory of the artist’s mother, Maya.

Traces of the past, layers of time and memory, biography and daughter-parents relations are central themes in Nurit David‘s oeuvre. In The Pharmacist, word paths wind like waves undulating downward, back and forth, left and right, engulfing a round photograph of the pharmacist—the artist’s father. In the left-hand side of the painting, close to the photograph featuring Nurit as a child, sentences gradually coil on themselves like a spiral, as if drawing into a concentrated focal point; wrapped and protected in another circle of sheaves. In order to read the text incorporated in the work, one must move the body and the head, thus linking the viewer’s consciousness, cognition, and soul with his body motion as it faces the work—a union of time and space.

The attempt to contemplate the boundary between body and soul, to fuse them into a whole, unified identity, and to indicate the difficulty and struggle along the way, are also at work in Etti Abergel‘s Soul Bodies. A jump rope functions as a spine or a lifeline, connecting upper and lower, heaven and earth, in a stubborn attempt to overcome gravity and the body’s limitations. In a strenuous work the artist sews together “muffin cups” to create a body: a scarred, cloven paper body; a map or parchment bearing streams of ink. The skip-rope handles remain, like a testimony—”Trees of Life”—preserving the memory of jumping and ascent.

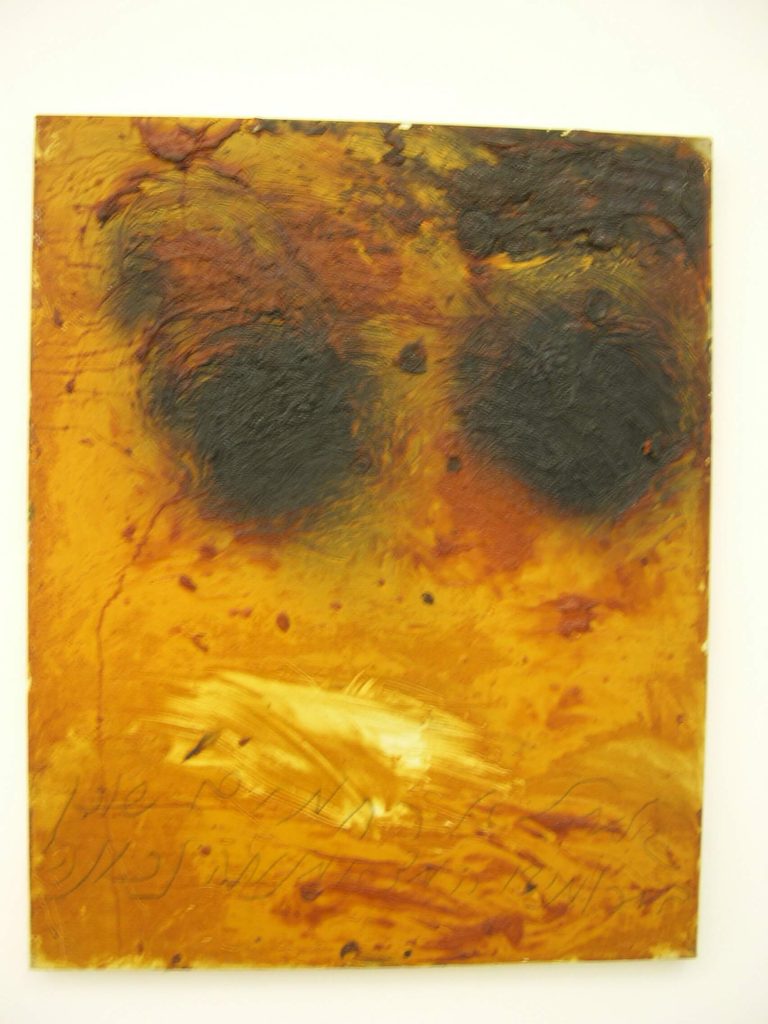

Moshe Gershuni‘s paintings emanate lines of prayer, as if erupting from the private and collective subconscious. A prayer is inscribed in pencil alongside a sensuous, lush and instinctual stain painting; a prayer of farewell from the deceased or a call to an existing or disappearing god. God or the appeal to the dweller of the heavens is inscribed at the bottom of the painting—as if it were buried in the ground. The painterly present, found in a vital, fresh, wild, spontaneous touch, encounters—via the inscription and the all-so-familiar verse—the past, its loss and traces, as well as the fear of what the future holds.

The defiled and disgusting inundate Assi Meshullam‘s works, which give expression to passion, to the forbidden and repressed, the filthy and fetid. Something primordial and sensuous bubbles out from his works, blurring the boundary between man and animal, culture and nature, prayer and sacrifice. His mezuzah returns to its origins—to the blood on the Israelites’ door frames in the Exodus story, or the parchment scroll on which it was inscribed—the skin of the slaughtered animal.

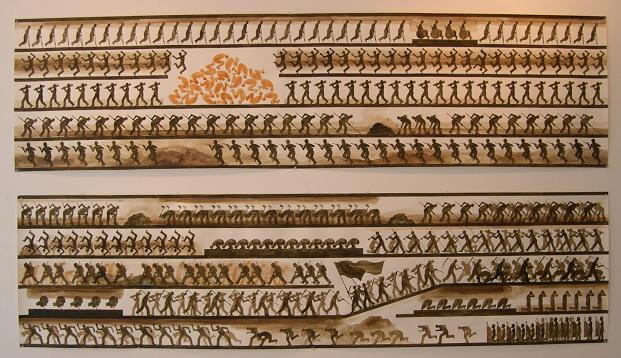

Questions concerning history also arise in Benni Efrat‘s project, Ararat Express, through the link between man and animal. Herds and caravans in constant motion, wandering, fleeing, scattering. The refugees of natural disasters, catastrophes, wars, and annihilation, head on toward an unknown destination like the condemned, in search of water, food, and shelter; an ongoing, closed circle which disseminated and duplicates itself via technology and progress.

“This is how the angel of history must look. His face is turned towards the past. Where a chain of events appears before us, he sees one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it at his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise that has got caught in his wings; it is so strong that the angel can no longer close them. This storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows towards the sky. What we call progress is this storm…” (Walter Benjamin).3

The occupants of Noah’s Ark, animals and man, move back and forth, over and over again, like a scroll that opens and closes, a time-line hung above a classroom blackboard, and an attempt to turn the wheel back, while indicating that “the past forever repeats itself.” And nevertheless, it is, Ararat, anticipating the water’s retreat.

The scroll in Michal Na’aman‘s work Daughter of Israel (Sandal) wraps her hands and clings to them like a second skin or as cuffs. Her raised arms stretch, unfurl, expose the written text. In handwriting, Na’aman copies a restrictive, disciplining pashkevil (admonitory wall poster used in Jewish orthodox neighborhoods) addressed to the “daughter of Israel” and her modesty. She is asked to cover her body, and her curious learning head remains outside the story, outside the picture. The threatening, reproving tone covers the body of the photographed figure, emphasizing the lowering, reductive point of view.

Love verses from the Song of Songs cut in iron transform into a body in Jack Jano‘s self-portraits. Long and narrow like bookmarks or like trampled swords, they lean against the wall; a figure whose body consists of letters and words and love sentences and a song—the Song of Songs. Words engulf houses like a garment—the houses of his childhood or the Tombs of the Just; houses in constant movement, houses which may, perhaps, find home in the letters.

Notes

- Yona Fischer, “Introduction,” cat. Moshe Kupferman: Paintings, Works on Paper (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 1984), p. 61.

- From a conversation with Yona Fischer, cat. Moshe Kupferman: Paintings and Works on Paper (Paris: Musée national d’Art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1987), p. 5.

- Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History” [1940], in Selected Writings, vol. 4: 1938-1940 (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2003), p. 392.