Looking Through – June 2022

Tsibi Geva, Yaacov Dorchin, Michal Rovner, Moshe Kupferman

The exhibition Looking Through sheds light on the work processes of the presenting artists – Tsibi Geva, Yaacov Dorchin, Michal Rovner, and Moshe Kupferman – and on common denominators informing their yearslong artistic endeavor. Multilayered, densely packed, prolonged and slow processes of veiling, unveiling, revealing and distilling the essence of the matter, and exposing “those things that carry weight”, in Kupferman’s words.1 Their relentless striving to arrive at the most precise essence of things is manifested in repetitiveness, daring and persistence, that do not subside until the realization

that something of value has been achieved, and they can therefore stop.

Dialogues with the artists in preparation for the exhibitions have indicated that they all have deep roots in the land, in the geographic local, roots that inspire many of their artistic choices and moves. For example, Geva’s reference to a tree from his childhood kibbutz landscapes, or Kupferman and Dorchin’s allusions to the kibbutz environment and its agricultural machinery.

And sometimes it is the title that exposes them, as in Dorchin’s “Mediterranean Landscape” or Rovner’s “Broshei-Har”.

Tsibi Geva’s works embody the artist’s painting history, as though clinging to it perhaps out of longing. In his works, Geva “implants” patches from previous works to generate an inner, personal dialogue between the past and present moment. He seems to play with time, unveiling it in a process of concealment and excavation that exposes deep layers from a different era. “Paintings are forever that which has already happened, their future is the past, which is a permanent present, neither a short

nor a long life”, says Dorchin with reference to Geva’s works.2

To create his sculptures, Yaacov Dorchin uses elements from various sources, fused together without completely losing the traces of their own history, accumulated into an independent set of images, melted down to bring a new and poetic object to life. In the course of his work, Dorchin studies the material and meets “these refugees of civilization have become junk”,3 discovering it and the baggage of human knowledge and experience imprinted into it.

In a manner almost contradictory to the nature of photography as documenting reality, Michal Rovner’s works evince a process of abstraction and the creation of a deep inner space, on which the eyes wander from within outwards, and from without inwards, refusing to focus. With their painterly qualities, her photographs present a blurry, layered state. Rovner uses the camera like a

paintbrush that produces only partly identifiable things, that are removed from their nature but nevertheless leave their reality traces behind, as an essence, a source, the basic form of themselves. As she puts it, “It could be anything, anywhere, a unit of life. I noticed that the more I erase, the more I reveal”.4

When you look at the exhibition in its entirety, a connection begins to emerge between the various media, which reflects a dialogue between matter and spirit. Thus, Rovner’s video work “Panorama” seems like a fresco, where almost nothing happens on the wall, but underneath the surface there is constant activity. Despite the toughness of the iron and the marks of the past

imprinted in it, Dorchin’s sculptures bear traces of the painterly linearism of a “painter who does sculptures”, as he has attested about himself, “in all of which there is this aspect of the bidimensional posing a tridimensional”.5 In Geva’s paintings, on the other hand, the boundaries of the two-dimensional are stretched both by the lumpiness of the paint and by the layering and depth formed as the result of imprinting canvasses from previous works onto the new ones. Finally, the multiple paint layers in Kupferman’s work sometimes create a multiplicity of planes, highlighting the depth dimension. The multilayered work process may be seen as “a perfectly organized methodology that asks about or searches for that ‘thing’, the place where the cut is made, where the pattern is betrayed, out of ‘the eternal recurrence of the same’.”6

What Kupferman has said about his own work is recognizable in all the works in this exhibition: “a process involving work, and more work and more work”, the “accumulated value of activity”.7 The works presented in the exhibition enable a multiplicity of readings, both in themselves and in a “looped” reference of the one through the other and through all.

Tal Bechler, Curator

:Footnotes

1 Yona Fischer (ed), Interpretations, Moshe Kupferman: Works from 1962 to 2000 (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 2002).

2 Yaacov Dorchin, “An Exhibitions That Leaves an Imprint”, Studio 101 (March 1999) (Hebrew).

3 Dorchin, as quoted in Dalia Karpel, “Iron Man”, Haaretz, May 14, 2009.

4 Michal Rovner, lecture at the Weitzman Institute of Science, (March 2009) (Hebrew).

5 Yaacov Dorchin, “Sculpture Garden”, talk with Hillit Yeshurun,Yaacov Dorchin Catalogue, Gan Aviyam, Dan Caesarea Hotel,

Gordon Gallery, 2019 (Hebrew).

6 Tsibi Geva, lecture on a symposium devoted to Kupferman’s work at Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem, 2008

(Hebrew).

7 Yona Fischer (ed), Kupferman in Interviews, Moshe Kupferman: Works from 1962 to 2000 (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 2002).

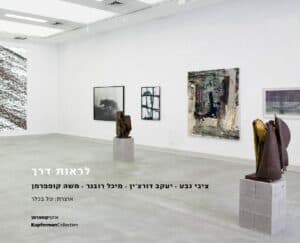

Looking through – installation view in the exhibition – Photo: Hadar Saifan